A Uniquely Christian Symbol: How Head Coverings Were Unfamiliar To Everyone

When we read 1 Corinthians 11, our minds usually wonder about the culture of Corinth and the general customs of that time. “Maybe this was peculiar to the situation in that city? Maybe women wearing head coverings were normative back then? Maybe a man with his head covered stood for something bad in that culture?” When these questions are raised, the interpreter often concludes that since in our time and culture coverings aren’t normative and men wearing hats are not frowned upon, that we are free to abandon or change the symbol to something more meaningful to us. Though there are exegetical reasons for not taking this route, there are also cultural reasons for why that simply doesn’t work. See, behind this assumption is a belief that what Paul laid out regarding head covering was culturally normative, familiar, and meaningful. That’s just simply not true.

What did first century Jews practice?

The head covering mentioned in 1 Corinthians 11 is a symbol peculiar to Christians under the new covenant. It was not instituted until after the new covenant was inaugurated and it was a radical change for Roman, Jewish and Greek worshipers of God. “Are you saying, they didn’t do this under the Old Covenant?” That’s what I’m saying. No where in the Old Testament are head coverings commanded for women nor were men forbidden from covering their heads.

Though Jewish women did cover their heads in the first century, Paul’s command is not for females only. If it was for cultural sensitivities that Paul made his command, it would have to match the cultural practice of both men and women. The fact is that there is no known first century cultural custom for Jewish men regarding their headgear.

Rabbi Abraham Ezra Millgram says:

“Though covering one’s head was regarded during the talmudic period as a sign of respect, there is scant evidence that Jews in the Temple court or in the early synagogue were required to wear any headgear.” 1) From Kippot (Head Coverings) in Synagogue accessed on April 20/15 at http://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/kippot-head-coverings-in-synagogue/

The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols also confirms:

“The High Priest wore a special head covering called a mitznefet (miter); the ordinary priest, a turban called a migbaat. But the ordinary Israelite was given no directions about head coverings.” 2) Ellen Frankel and Betsy Teutsch – The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols (1992, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers) Page 91

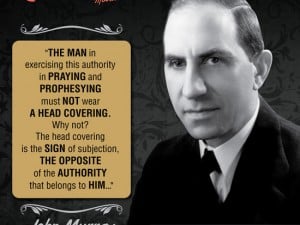

If there was no custom, that means some men would have covered their heads while others would have not. Neither would raise any eyebrows. This does not line up with 1 Corinthians 11 where Paul forbids men to cover their heads while praying and prophesying (1 Cor 11:4). It was not until the time of the Talmud (3rd century) when the Jewish custom of head covering for men emerges. This custom was the exact opposite of what Paul commanded and is still being practiced today. The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols said that the custom arose “largely as a reaction to the Christian practice of praying bareheaded.” 3) Ellen Frankel and Betsy Teutsch – The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols (1992, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers) Page 91

What did first century Greeks and Romans practice?

You may be thinking, “Well Corinth was a church with a lot of Gentiles so maybe it was the non-Jewish Christians he had in mind.” On exegetical grounds it’s hard to accept this as he appeals to all men and women (v. 4-5), not just Jews and Greeks. He also appeals to what “all the churches” practice (v. 16), not just one church or one region. But laying that aside, the head covering command was a huge change for the Gentile worshiper as well.

Tertullian was a Christian who lived in the 2nd century. He was fully aware of the customs of the day regarding head covering and wrote about them. He said:

“Among the Jews, it is so usual for their women to have the head veiled that this is the means by which they may be recognized.” 4) Tertullian, De Corona ch. 4, Anti-Nicene Fathers Vol. 3 at 95.

When Tertullian says that a Jewish woman is recognized by her veiled head, this tells us that for Gentiles, it was not their custom. If you can be recognized by what you’re wearing, it implies that everyone else does not wear the same.

Numerous biblical scholars and historians also confirm the fact that the instructions for men and women in 1 Corinthians 11 do not match Gentile practice. Both Greek men and women uncovered their heads while worshiping their gods, whereas Roman men and women would cover their heads while performing public religious acts (like a sacrifice). So no matter which major people group we look at, neither matches Paul’s instruction for both sexes.5) For a list of sources for Jewish, Greek, and Roman practices see “Covered Glory” by David Phillips pages 67-74. That’s because it was a Christian practice, not a cultural one.

The Cambridge Bible for Schools and College summarizes this by saying:

“the remarkable fact that the practice here enjoined is neither Jewish, which required men to be veiled in prayer, nor Greek which required both men and women to be unveiled, but peculiar to Christians.” 6) The Cambridge Bible for Schools and College – First Epistle to the Corinthians (Page 158 – accessed online here.)

A new practice

So the head covering practice would have been different for Jewish men, Roman men, and Greek women. Jewish and Roman men who followed Christ now had to remove their covering during worship for the first time. Likewise, Greek women had to start covering their heads in worship for the very first time.

Dr. Ben Witherington III highlights the uniqueness of this practice by saying:

“Paul is not simply endorsing standard Roman or even Greco-Roman customs in Corinth. Paul was about the business of reforming his converts’ social assumptions and conventions in the context of the Christian community. They were to model new Christian customs, common in the assemblies of God but uncommon in the culture, thus staking out their own sense of a unique identity.” 7) Ben Witherington III – “Conflict and Community in Corinth” (Eerdmans, 1995) Pages 235-236

It’s hard to believe that Paul would insist on a symbol that was unfamiliar to all groups, the very opposite of what they were accustom to, if he did not intend for it to be carried on. The “contentious” people advocating a different practice now become a little more understandable. People don’t become contentious over what is the normative practice, they become contentious when you take away their normative practice and ask them to do something different. The practice of head covering was as radical in Paul’s day as it is in ours!

How do we treat other symbols?

When we plant a church in a foreign land for the first time, we understand that Baptism and the Lord’s Supper will have no meaning to them in their cultural context. After all, it shouldn’t, as they are Christian symbols which find their base in Scripture. So what do we do? Do we abandon the symbol and instead just teach them what the symbols point to? After all, the meaning behind the symbol is what’s most important. We don’t though, do we? Maybe we shouldn’t abandon the symbols but instead replace Baptism and the Lord’s supper with something more culturally meaningful? But we don’t do that either. When we enter an unreached area, we still Baptize believers and break bread with them because these are Christian symbols. We understand that to them it has no cultural meaning, so we instruct them from the Scriptures on what the symbols mean. The same should be done for head covering.

References

- Is Head Covering Related to Spiritual Gifts? A Response to Barry York - July 5, 2023

- A Husband’s Authority is Limited (He is Not Pastor or King) - November 14, 2022

- Statement from Jeremy Gardiner: Leadership Transition - September 26, 2022